With the tremendous buzz around the political, social, and economic factors at play around ESG (“Environmental, Social, and Governance”) bonds and their evolving status, it can be daunting for muni bond issuers that may want to enter this niche of the capital markets. The municipal bond market is, in fact, undergoing a period of change on how it both grapples with and takes advantage of ESGs. While we expect this transition to be a slow one, the market is indeed moving toward greater acceptance of ESGs and ESG labeling, albeit through the counteracting pressures of both growing demand and political resistance from national and state actors. Here, we discuss the factors at play for higher education institutions, including the varying levels of commitment and the pros and cons evident in the ESG muni bond market, both economic and otherwise.

ESG-labeled bonds are frequently referred to as green or social bonds, which have been a part of the muni market since 2013 when the Commonwealth of Massachusetts issued the first green bond in the United States.[1] Indeed, labeled issuance has grown significantly in just the past few years, accounting for 2% of all issuance in 2018 to almost 11% at the end of 2022 (albeit lower in absolute levels in 2022 versus 2021).[2] It is no wonder that this burgeoning market has attracted attention from all muni issuers, including higher education institutions.

Those issuers keen to participate in this growing market have readily available standards for contemplated ESG labels. One such measuring stick is the International Capital Market Association’s (ICMA) standards via the Green Bond Principals, Social Bond Principals, and Sustainability Bond Guidelines. Issuers seeking to employ these standards must voluntarily meet four pillars that touch on the use of proceeds, project evaluation and selection, management of proceeds, and reporting. For the standards set by the Climate Bond Initiative (CBI), issuers must demonstrate how the project contributes to the Paris Agreement’s goal of reducing carbon emissions and creating a climate resilient economy; unlike ICMA’s voluntary standards, these bonds must be reviewed by an approved verifier for conformity to the ICMA Green Bond Principals and the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. Third-party verifiers can assist through the entire process of evaluating a project through the lens of any of these standards, from the initial evaluation through execution and beyond with post-issuance reporting. Some verifiers have additional fees, while others, such as BAM’s GreenStar, provide green label services free for its eligible insured clients. Other muni bond issuers take the DIY route, however, by “self-designating” their bonds, without reference to the above external guidelines. These self-designated bonds often include project-specific standards; for example, the official statements may reference LEED-certified construction projects.

Once the bonds have been issued, depending on the selected standards, there may be ongoing post-issuance obligations. These are primarily continuing disclosure obligations about the project. The more stringent CBI standards require that a verifier submit one report on proceeds within two years of issuance, afterwards followed by annual reports until maturity. Issuers who use ICMA standards are strongly encouraged, but not required, to make annual reports available to investors. Third-party verifiers can do the lifting on these obligations, too. Of course, self-designated bonds can opt to issue updates on ESG projects or not.

At this stage of development, data and disclosure issues form the crux of the current conflict between issuer and investor. On the buy-side, investors continue to demand more information and coordination across the muni market so that labeled bonds are more systematically comparable.[3]Investors want common data and standards and prefer ongoing disclosures to ensure bonds aren’t being “greenwashed.” Issuers, on the other hand, hope to be compensated for the trouble of providing the data and updates requested; as we shall see, the additional hassle of issuing green and social bonds isn’t always rewarded economically. For both, the learning curve continues, and so far government actors have done little to provide sufficient guidance on how ESG label disclosures should be conducted. And until the market develops further, investors may not be willing to pay up for green and social labels.

For all the additional cost and trouble, what do green and social bond labels actually bring to the table for issuers? Theoretically, ESG-labeled bonds should attract more investors, generating lower yields at issuance. In fact, despite the noise around labeled bonds, there is little evidence for any “greenium” (a portmanteau: “green” + “premium”) for higher education issuers. For starters, for any deal it is extremely difficult to demonstrate that the label has any effect without one or more very similar comparable deals – a tall order. The effect may not be evident without looking behind the curtain, either. In one case last year, St. Thomas University (MN) issued a $131 million deal with two nearly identical series, one with a green label, the other without.[4] According to participants, while the two series had no difference in pricing, the green bonds possibly pulled in more investors, some of whom ended up buying the non-labeled bonds rather than go home empty-handed.[5] There is anecdotal evidence that an outright ESG premium can be achieved; in 2021, Oberlin College (OH) issued $80 million in green-labeled (CBI) bonds. According to the verification agent Kestrel, despite a five basis point repricing for Oberlin’s green bonds, the anchor investor for the deal opted to put in an order for all of the Oberlin bonds instead of selecting similar non-green and self-certified bonds on the capital markets at the same time.[6] But save for a few anecdotes like these, issuers – including in the higher education sector – currently cannot count on green- or social-labeled bonds generating any additional premium.

What can environmental or socially conscientious issuers do? We suggest muni issuers continue to watch this space closely. There is a growing demand for ESG-labeled bonds, but uniform standards and cross-market coordination lack to such a degree that one cannot count on an accompanying pricing premium. The lack of a clear premium means the choice to use ESG labels may lie outside the economics of the deal itself. Some issuers may want to demonstrate leadership in the use of green or social bonds, showing their commitment to environmental or social justice goals. These institutions should carefully decide if their transaction warrants the additional cost of a third-party for verification or if they are comfortable with the self-designated route, with fewer costs but possibly less desirable to investors and not signifying the full-throated commitment to green or social aims. For those issuers that will only consider ESG labels when there is a clear case for an economic benefit, waiting for the market to develop – either within the sector or from other muni bond industries – makes more sense.

If your institution is weighing the decision to engage in green or social labels for an upcoming issuance, we would be pleased to help you better understand the pros and cons that are unique to your goals and transaction. Please give us a call.

Comparable Issues Commentary

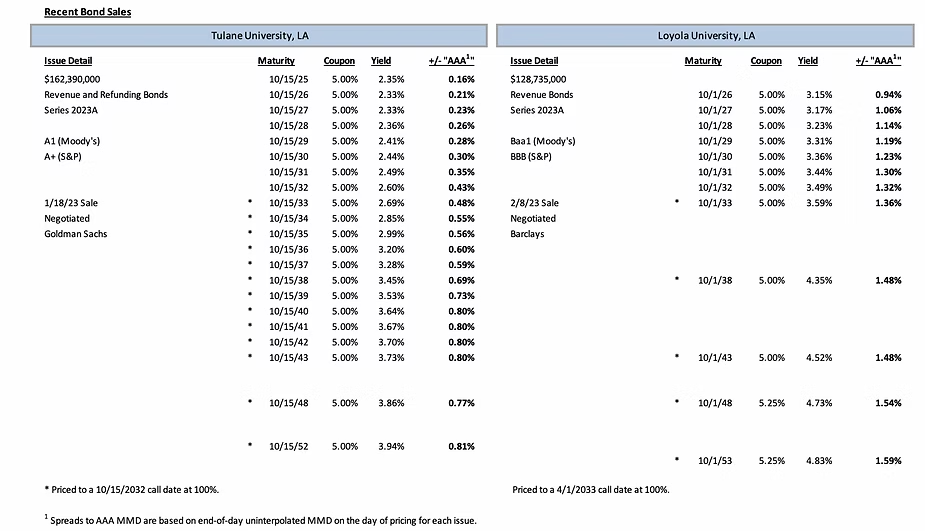

Shown below are the results of two private higher education financings that have priced so far this year from the State of Louisiana. In fact, both are neighbors, located in the Uptown area of New Orleans. On January 18th, Tulane University (“Tulane”) priced its tax-exempt Series 2023A Revenue and Refunding Bonds. Three weeks later on February 8th, Loyola University of New Orleans (“Loyola”) priced its tax-exempt Series 2023A Revenue Bonds. Tulane’s transaction was a multi-purpose issuance that financed the construction of new student housing facilities (adding up to 1,000 beds on its Uptown Campus) and the renovation of a historic academic building on campus. The deal also refunded a portion of the University’s outstanding Series 2013B bonds and funded a capitalized interest fund. Loyola’s issuance was a purely new money borrowing serving to construct and equip a new residence hall on campus (adding 610 new beds as well as a community center) in addition to funding renovations at several other campus buildings. Proceeds from the issuance will also be used to capitalize interest until October of 2026.

Both schools’ bonds carried ratings from Moody’s Investors Service (“Moody’s”) and S&P Global Ratings (“S&P”). Tulane’s bonds were rated “A1” and “A+” by Moody’s and S&P, respectively, while Loyola’s bonds were rated several notches lower at “Baa1” and “BBB.” Given the many similar aspects of these two deals, the credit differential between the schools was a key difference maker in the outcome of their bond pricings. Both series were sizeable deals totaling over $100 million in par amount. Tulane’s deal was the larger of the two at $162.39 million, while Loyola’s deal was $128.735 million in total par. Both transactions had a final maturity of approximately 30 years, but had some differences in underlying structure. Tulane’s Series 2023A was serialized from 2025-2043 with two term bonds in 2048 and 2052. Loyola’s Series 2023A featured serials from 2026-2033 with four term bonds in 2038, 2043, 2048, and 2053. The pace of amortization for the two transactions differed markedly, however, with Tulane amortizing three large serial maturities ranging from $9.6M – $20.5M in size from 2035-2037. In contrast, Loyola’s annual principal payments remain below $2M/year through 2046, after which they spike sharply, increasing to anywhere from $12.2M – $19.2M thereafter through the final maturity in 2053. Tulane’s bonds have a nine-year call in October of 2032, while Loyola’s bonds become callable 6 months later in April of 2033. The coupons used in both transactions were almost exclusively 5% coupons with the exception of Loyola’s final two term bonds, which carried 5.25% coupons.

The week before Tulane’s pricing in mid-January, MMD fell by 11-19 bps across the yield curve. During the week of pricing, it held steady prior to Tulane’s bond sale on the 18th before dropping by an additional 8-10 bps across the curve on the pricing date itself. Tulane was ultimately able to achieve spreads of 16-80 bps on its serial maturities and 77 and 81 bps on its 2048 and 2052 term bonds, respectively.

Between Tulane’s pricing and Loyola’s bond sale three weeks later, the MMD curve inverted further on the front end of the curve, with the 1 and 2-year tenors increasing by 6-18 bps while the 3 to 12-year tenors were effectively unchanged (with movement of just ±2 bps on those maturities). The longer end of the curve also increased, with the 13 to 30-year tenors rising by 9-11 bps overall during the period. On Loyola’s pricing date the index was relatively stable, increasing by 5 bps in 2024 and 2025 and 3 bps in 2026, but remaining unchanged for all other maturities. Ultimately Loyola was able to achieve spreads of 94-136 bps on its serial bonds and spreads of 148 bps on both 2038 and 2043 term bonds, 154 bps on its 2048 term, and 159 bps on the 2053 term bond. On overlapping maturities, Loyola priced anywhere from 68-95 bps wide of Tulane with an overall average spread differential of 84 bps on those maturities.

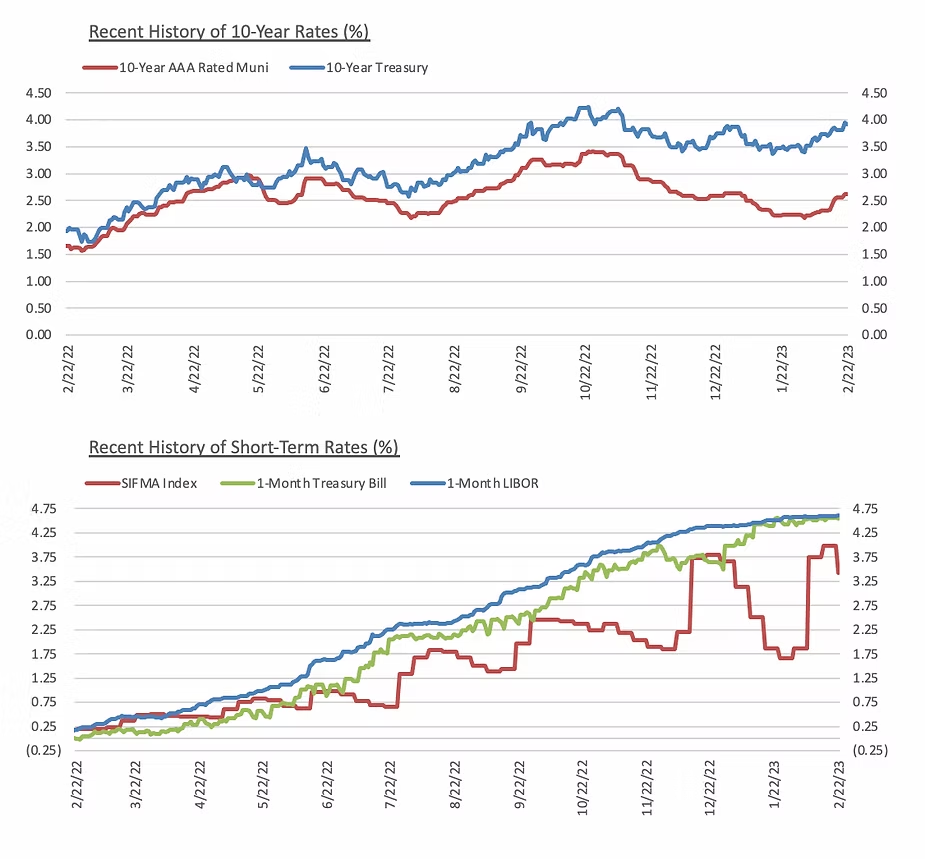

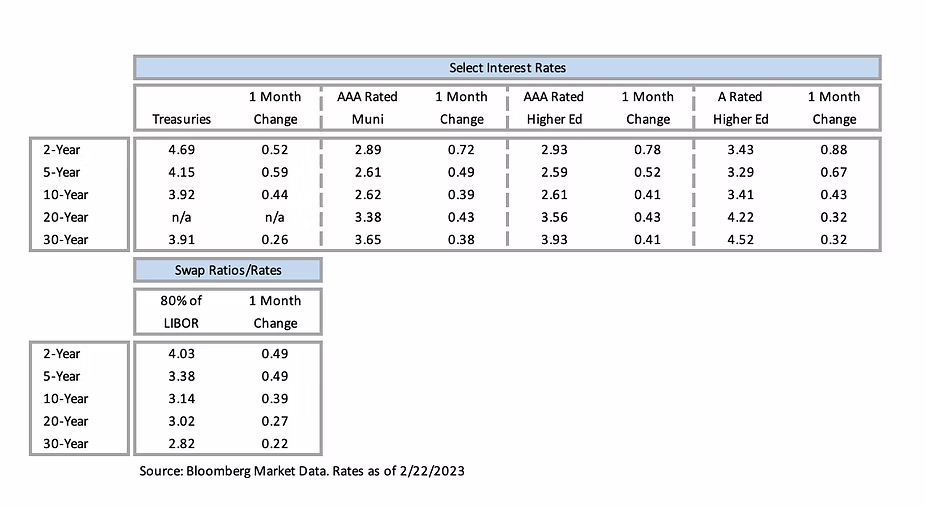

Interest Rates

Meet our Author:

John Elliott | [email protected] | 952-460-5776

In his role as Chief Compliance Officer, Mr. Elliott is tasked with maintaining responsibility for client contracts and disclosures. He will continue to provide analytical and research support for Blue Rose’s P3 and debt advisory practice and will also serve on the project team by providing expertise in documentation review and legal requirements for many of the firm’s clients.

Media Contact:

Megan Roth, Marketing Manager

952-746-6056